In the first part of this file, we discussed the basic electronically adjustable suspension, with presets for spring preload and damping adjustments, but also the semi-active self-adjusting systems, which automatically adjust the damping to better ride. adapt to the road surface and driving maneuvers. But since when did all this exist? And which motorcycles are equipped with it?

All manufacturers adopt it…

BMW was one of the first manufacturers to offer electronic suspension adjustment, on the K1200S and R in 2004. The ESA electronic suspension adjustment system had a series of presets on the dashboard, for solo, duo and/or configurations. with luggage. The ECU sent signals to small electric motors to operate adjusters on the shock absorbers (rear and front Telelever), providing stiffer damping changing preload and even spring rate. This was about convenience and ease of adjustment for different loads. On this type of motorcycle, the forks and shock absorbers are hidden under plastic panels and are difficult to access. And unlike a more sporty motorcycle, it is usual to load a BMW or a Goldwing with more than 100 kg for a ride, if we take into account the passenger and the suitcases. So it makes sense that there would be a need for radical suspension setup changes, and they would be a real pain without electronics. Replacing the lug wrench and screwdriver in the tool box with neat push buttons is the perfect solution for a high-end touring motorcycle.

Damping is adjusted using proportional damping valves with “variable annular space and therefore variable flow rate for the shock absorber oil”. These valves allow the damping force to be changed in just a few milliseconds.

The second generation of the German system (ESAII) was released in 2007 and found its place on the K1300S. But it wasn't until 2013 that BMW really improved its system, introducing its much more sophisticated semi-active dynamic damping control setup on the HP4 Superbike in 2013. This was the first time the suspension was actually adjusted based on feedback from the spring travel sensors, instead of just playing with predetermined damping positions. This was a huge breakthrough that set the standard for the industry using an elastomeric spring rate adjuster. A steel axle moves through a rubber-like material, which actually changes the effective spring rate of the monoshock. Moving this pin out of the elastomer makes it "softer", which reduces the overall stiffness of the spring. This is different from adjusting preload, and before ESA this could only be done by swapping out the metal spring itself.

Like the Multistrada, the HP4 has an electronic valve in just one fork leg, while the other has a preload adjuster on top. The computer obtains all its information from the sensors already on board and from part of the ABS and Traction Control of the HP4: speed, lean angle, accelerometers, braking pressure, etc.

Introduced at EICMA in 2012, Marzocchi's semi-active suspension version entered production in 2015, with the intention that its components would be self-contained and could be used as an upgrade on an already mass-produced model.

The system uses potentiometers and an inertial platform for a complete picture of the motorcycle's acceleration and cornering position angles. To go further, GPS is also integrated. A dedicated ECU analyzes all this data, and a smartphone or tablet can be used to make general changes to the system, direct adjustments to settings, or even changes to the actual damping curves of the fork and shock. This would make the system much more adjustable and even more suitable for racing applications.

Marzocchi developed his own version of semi-active suspension

Electronic valves developed by Tenneco, Marzocchi's parent company, are used to control the damping: the response time is less than 10 milliseconds, in the same order as the BMW and Ducati systems. Marzocchi works with a variety of manufacturers, including BMW, Ducati, Harley-Davidson, Piaggio (Aprilia) and MV Agusta. Documents on Marzocchi's site show the semi-active system deployed on an MV Agusta Brutale model, and it is also used on the MV Agusta Turismo Veloce 800. Ironically, Tenneco has its own semi-active system called Continuously Controlled Electronic Suspension (CES) which is used in many automotive applications, and the CES valves – probably the same ones used in the Marzocchi system – were developed in collaboration with the Öhlins racing department.

We can't talk about high-end pendant lights without talking about the Swedish brand, Öhlins. It's been almost 30 years since Öhlins first experimented with semi-active suspension on Yamaha Grand Prix bikes, but the technology has been standard production ever since. Öhlins presented its mechatronic (mechanical and electronic) system at the end of 2011 for the BMW R 1200. At the same time, BMW took a step beyond its electronic suspension adjustment (ESA) and released information on a new Dynamic Damping Control (DDC) system. Mechatronics and DDC work on the same basic principle: changing suspension action in real time to better adapt to conditions, based on data collected from various sensors.

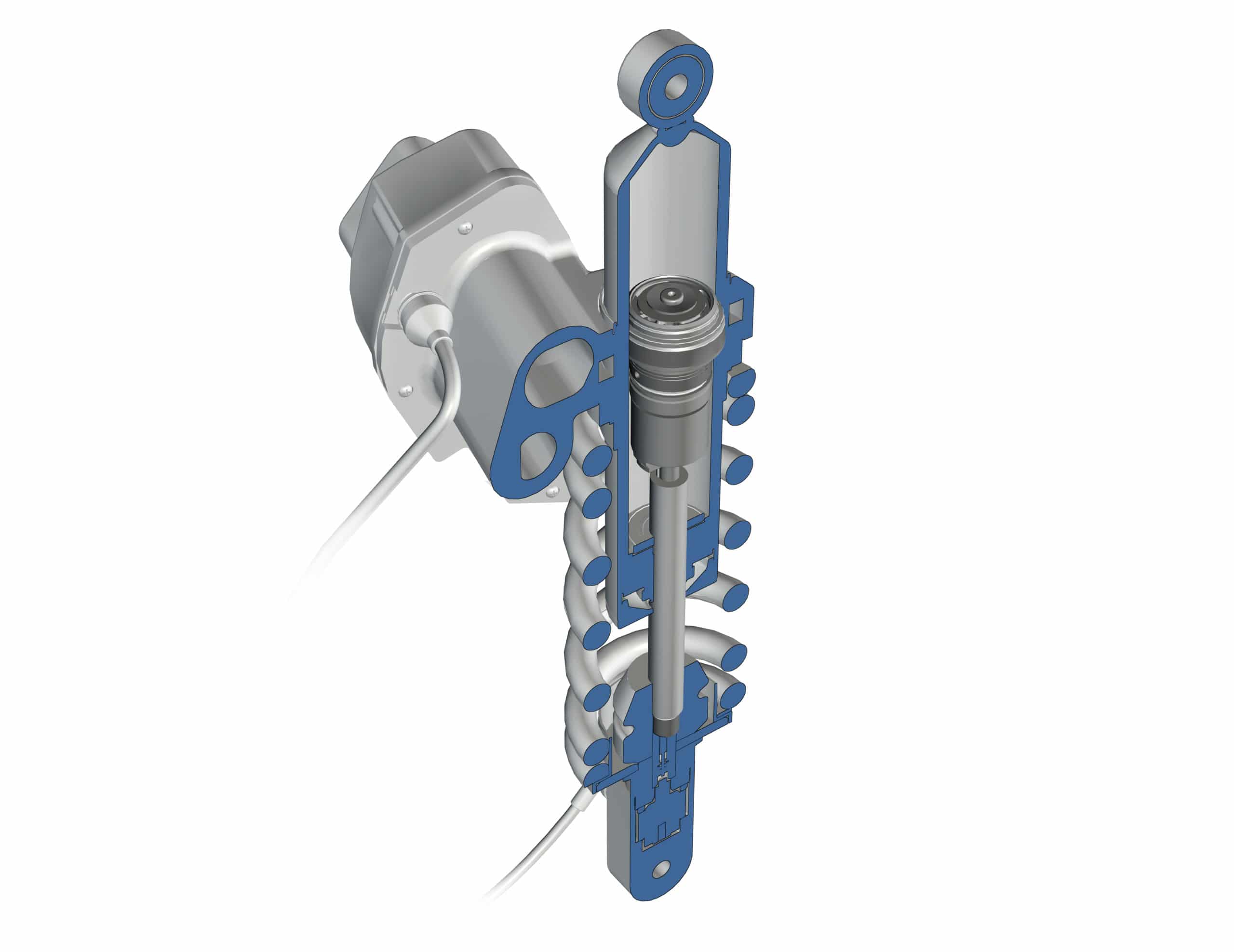

Öhlins uses small stepper motors to change the damping settings in the shock absorber. This is the TTX36 shock absorber offered for the Kawasaki ZX-10R.

Öhlins' mechatronics system starts with the TTX shock absorbers, with the compression and rebound adjusters replaced by small stepper motors. The technology, dubbed TTX EC (Electronically Controlled), has already been used on Yamaha snowmobile models and is part of Ducati's electronic suspension package on the Multistrada and Panigale models (1199 and then the V4), which allows the rider to modify settings via the dashboard. The R1M is also equipped with these gold shock absorbers.

With mechatronics, however, the stepper motors take their commands from a dedicated computer. The system was first used by the Yamaha World Superbike team in 2008 (see image below), and is now offered as a kit for the ESA II-equipped R 1200 GS – which has a Telelever front fork and can use two TTX shock absorbers.

KTM also has an electronic suspension system, produced by WP. The forks and shocks themselves are built by WP, and the system uses Bosch's electronic control unit, with software calibration by WP. Its semi-active suspension is fitted to the Adventure S (since 2015), as well as the original 1290 Adventure. The 1190 Adventure also comes with an electronic preload fit from 2013-16. But KTM doesn't just reserve it for adventure bikes, as the Austrian brand also installed electronic suspension on their SuperDuke GT, which proved to be a winning combination.

KTM has equipped the SuperDuke GT with a semi-active suspension, via its subsidiary WP

Like any technological development, each manufacturer is interested in it, to align with the competition. In 2018, it will be Kawasaki's turn to enter the electronic suspension field, thanks to Showa and an exclusive agreement between the two companies. The 10 ZX-2018R SE features an all-new semi-active Showa electronic suspension system. The rear monoshock and front forks both have computer-controlled damping adjusters, but they use a new solenoid-style setting. Much of today's technology uses small stepper motors, connected to the damping screws: a small 12V motor does the work a mechanic would do with a screwdriver on a manual suspension, with varying degrees of clicks. But Showa uses a solenoid to adjust the shocks. This is a faster, more direct mechanism that responds within milliseconds.

The Showa suspension elements that equip the Kawasaki ZW-10R SE

Showa also equipped its new shocks with travel sensors, small electronic devices to measure suspension movement. This information is then sent back to Showa's own ECU, so the computer knows what position the wheels are in, how fast they are moving and whether they are accelerating or decelerating. This information is combined with other inputs from the ZX-10R's main ECU covering speed, throttle position, braking – and it also looks at the bike's IMU unit, which tells it the angle tilt, as well as its pitch and yaw. Technical, right?

What is the next step ?

Many of today's "dynamic" electronic suspension systems are intelligent – but not as intelligent as one might hope. They simply adjust the suspension based on a number of factors – speed, throttle position, braking – but they lack a critical engineering concept called "feedback." In other words, they don't know exactly what's going on with the wheel, because they don't have a position sensor on the shock absorber.

You've probably seen these types of sensors on MotoGP bikes, where they are used for data recording. Called LVDT (Linear Variable Differential Transformer), these long rods look a bit like a steering damper, and they measure the damper's travel continuously, storing the information so technicians can analyze the data when returning to the pits. of the pilot.

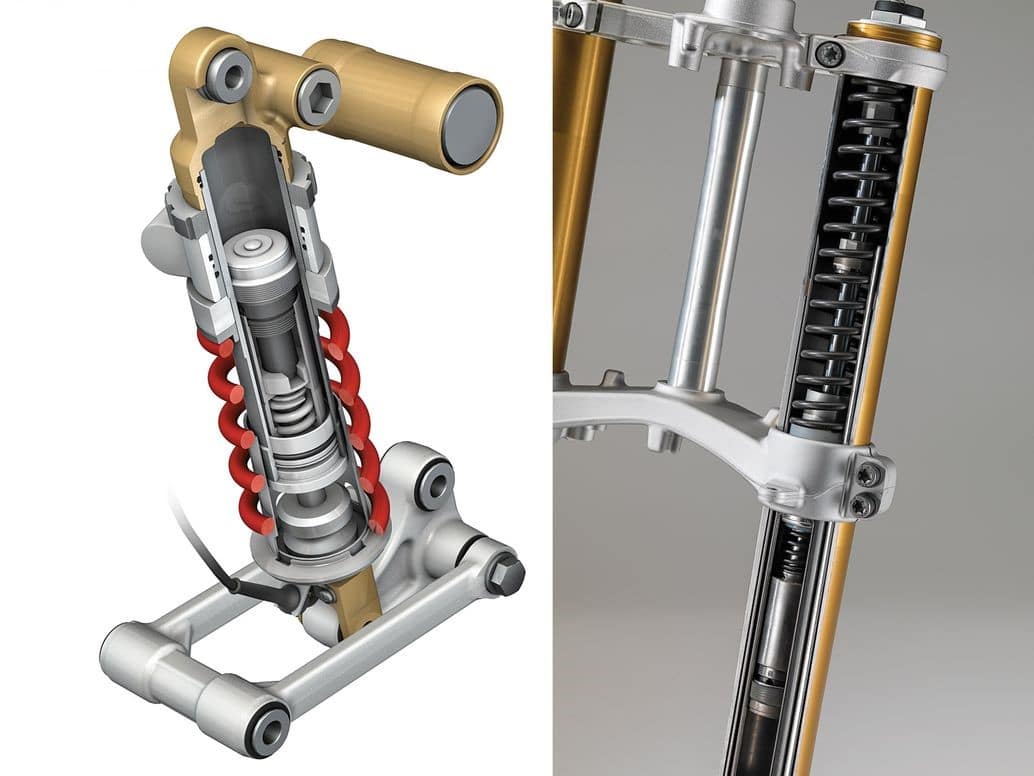

The “red rod” is an LVDT and is clearly visible on this Yamaha YZR-M1 twin rear shock

Now, if our electronic suspension system was equipped with this, it could immediately see what's happening at the wheel, rather than having to interpret it from all the other factors.

With a fast enough ECU and super-fast-acting damping adjusters, it could react much more quickly and efficiently to bumps, braking and acceleration than ever before.

The Showa setup on the new ZX-10R SE comes with this type of setup: stroke sensors in the fork and shock, and a new solenoid damping adjustment mechanism, which promises to respond within milliseconds .

What about the competition?

This is all very practical, but even if weight wasn't an issue, why don't MotoGP riders use it? The answer is quite simple: the suspension of a high-level racing motorcycle is correctly configured for a given race track, low in bumps and known to suspension technicians. It's a fairly simple problem to solve, setting up a motorcycle for a rider and their riding style. Indeed, technicians could undoubtedly achieve a slightly better setup for each corner with electronic adjustment.

But would that make up for the additional mass, cost, complexity and setup time required? Probably not. Either way, the regulations are overwhelmingly against electronic suspension setups. In World Superbike, they can only be used if they are also present on the homologated version of the machine – and, above all, only the homologated configuration can be used, without modification of the ECU or the shock absorbers themselves (at the same time). (except for valves and fluid changes).

GPS – or any other information regarding the position of the motorcycle on the track – is not permitted for suspension adjustment. This means that it is not possible to have a setting that adjusts the suspension parameters for each curve. Also, this means that in WSBK, riders must ride a bike with extra weight, with a road bike setup and it is not possible to modify it specifically for racing. This is why we see so few of them on the track.

In 2008, Noriyuki Haga used Öhlins Semi Active Suspension on his WSBK Yamaha YZF-R1, with a shock controlled by this ECU (the golden box) nestled inside the seat shell. In this application, three-axis gyroscopes help determine when and how to adjust damping.

In Grand Prix, it's even simpler: no electronic suspension is allowed, whether in Moto3, Moto2 or MotoGP. What limits the introduction of such technology is above all its exorbitant development cost, which would further widen the gap between teams with big budgets and small satellite teams. However, you should never say never. If suspension manufacturers (Öhlins, Showa, WP, etc.) spend more and more money developing these kinds of systems, they may well start to push for their inclusion in the racing world. The point of racing is, after all, to develop new technologies to adapt them to production motorcycles, but also to publicize a brand for the commercial side. So, the presence of super intelligent semi-active suspension on a MotoGP prototype would make this system more attractive on a production motorcycle. For now we can only assume, but as electronic suspension becomes standard on road-going Superbikes, we can only assume we'll see them in competition one day. As for mass-produced motorcycles, it is possible that this will become the norm in a decade at most.

Sources: BMW, Ducati, Aprilia, BWI Group, Öhlins, Marzocchi, WP, Sachs, etc.