Kalex is the chassis brand that wins in Moto2. But why do many teams use this chassis? Without a doubt, the decision on which chassis to use is a very important decision. However, the fact is that there are many major factors that determine a driver's racing performance, not least the engine. And since everyone in Moto2 must use the same engine, the chassis is important.

Kalex has already celebrated 114 victories in the Moto2 World Championship and has won all 14 titles (riders' and constructors' championships) since 2013.

The German company Kalex Engineering, located in Bobingen, won the 2 Moto2011 Drivers' Championship for the first time with Stefan Bradl, then since 2013 (Pol Espargaró) the seven consecutive titles in the Moto2 category (brands and drivers). Kalex celebrated his 100th GP victory last year and the Moto2 record now stands at 114 GP victories. And thanks to Tetsuta Nagashima of the Red Bull Ajo team, Kalex also leads the 2020 world championship.

Kalex employs nine people in total and the 2020 machines have been delivered. But the Moto2 World Championship ended after just one race, in Qatar. While waiting for the season to resume, let's focus on this winning chassis.

A glimpse into History

The 60cc category had existed for 250 years when it was replaced in 2010 by a new category and a new concept. Historically, the previous categories, 125, 250, 350 and 500, existed to showcase the range of production motorcycles currently in production. At that time there were riders like Ángel Nieto or Giacomo Agostini who spent their careers in one or two categories – the first in 125, the second in 350 and 500. Each manufacturer in each category had developed its own racing motorcycles , including their engines.

In 2010, all that changed. From now on, the world championship categories are ladders to climb leading to MotoGP. Promising new riders would start in Moto3, limited to 250cc four-stroke singles. The winner would move up to Moto3, all of whose machines would be powered by identical Honda CBR2RR inline-four engines, in a handcrafted chassis of the team's choice. Those who progressed to MotoGP would ride real prototype motorcycles, each designed and built by its own brand.

These changes eliminated the expensive engine development that had previously made the 125 and 250 classes so exclusive. It was even hoped that Moto2 would unleash a storm of chassis innovation.

Kalex's Moto2 chassis won the first Moto2 race in 2020 (but also claims the next 4 places...)

There was definitely chassis innovation in Moto2, but you had to look closely to see it. But although visually it was not obvious, it was important.

In 2019, the Moto2 category changed engine manufacturer, moving from the Honda 600 engine to that of the Triumph 765, requiring the development of new chassis. The first (and so far, only) Moto2 race this year – at the Losail circuit in Qatar – was won by Tetsuta Nagashima on a Red Bull KTM Ajo team entry in KTM livery, on a chassis double-beam aluminum frame developed by Kalex Engineering (Kalex has had a long history of cooperation with KTM). And that's not all. The first five were equipped with Kalex chassis. Even better, of the 25 finalists, 17 drove machines equipped with Kalex chassis, or 68% of the drivers registered in Moto2.

Kalex is the chassis to have in Moto2

The Speed Up chassis drivers finished sixth and eighth. KTM, faithful to the latter with its welded steel tube chassis, withdrew its own chassis from the category at the end of 2019.

All frames in this class are beautifully crafted, displaying the highest class of mechanical and welding work while having flowing shapes that best resist the cracking inherent in aluminum structures.

The Kalex chassis in its simplest form. He is currently the most efficient in Moto2

But why is Kalex the chassis to have in Moto2? Sam Lowes said: “If our tuning was perfect the Speed Up would be as good as the Kalex. But 99,9% of the season it wasn't an advantage to be on this bike, because our adjustment window was much narrower than Kalex's. One weekend my bike was just awesome and the next I had no chance. »

Lowes also noted that due to the high number of different drivers equipped with Kalex, this manufacturer's information base is very large. It is also possible that Dunlop, which supplies tires in Moto2, will do what comes naturally in competition: design tires suitable for the best.

Swiss driver Thomas Lüthi drove a Suter chassis in 2017, but the manufacturer then left the category. Lüthi said, just before the 2018 season: “When I moved to Kalex, I think it could have been a little worse but we found more consistency, and that's the consistency I was looking for. »

“If you find perfect or near-perfect chassis tuning on the Suter, then the bike is really great. If you have a bad day with the setup on the Kalex, you can still get on the podium, but if you have a bad day with the setup on the Suter, then you would be fighting to be in the top 10.”

This has its parallel in the world of off-road cars. A car with a more flexible chassis is easier to adjust, while a car built with a more rigid chassis (influence coming from F1) requires much more of its suspension and is therefore more difficult to adjust to go quickly.

Lüthi said the Suter chassis, when tuned correctly, was more precise than the more MotoGP-like Kalex. Before adding: “But finding this configuration is damn difficult. The Kalex is not as precise and it moves more, but you can go very fast. »

The Suter chassis is more precise than the Kalex, but much more difficult to adjust to be effective

Less precise? More movement? These are the criticisms that Casey Stoner made in 2008 about the Ducati's relatively flexible tubular steel trellis frame: "On this thing, you can't have the same trajectory on two consecutive turns. »

A big part of this is surely the delay in steering feel that a certain degree of chassis lateral flexibility imposes.

Looking down on the Kalex chassis, one is struck by how much the thickness of its side beams is shrinking. This taper places most of the bending at the back of the beams.

Looking at the mounting points at the front of the engine, they become quite thin at their ends. It's as if the front chassis is a fairly rigid four-legged "spider", surrounding the engine and with the steering column at the front. At its ends it has flex zones that provide the lateral movement that helps keep the front tire in contact with the track.

Changes visible in recent Moto2 chassis include the opening of the caster angle to provide additional volume to the airbox. The steering column itself is made narrow so that carbon ducts mounted on either side can send air from a central air intake to the airbox, with minimal energy loss.

Since 2014, Moto2 teams have started to cover the side faces of their frames with carbon fiber in order to increase the resistance to pinching of the steering column due to the forces during hard braking.

Everyone uses carefully machined parts that allow precise control of thickness – more frames assembled from a machined steering column added to two extruded uprights of constant section and length that formed the side beams. Where should the bending occur, how should it be distributed and how can we know the limit between bending and breaking? As they say in F1, "To design next year's winner, you must have designed last year's winner." »

The chassis of the Moriwaki MD600 in 2010 was a mix between the stock CBR and the RCV212V

In 2010, the first year of the Moto2 category, the Moriwaki chassis closely resembled the chassis of the production CBR600RR and that of the 212 MotoGP RC2009V prototype. All of these designs shared the longer engine support rails which are an element allowing the steering column to flex laterally by a few millimeters – an innovation from 2002. In 2010, the Gresini team and Toni Elias won the first Moto2 championship on the Moriwaki chassis while Kalex failed to score a single point. In 2012, competition from other chassis manufacturers pushed Gresini to switch from Moriwaki to Suter.

How can a designer know the side effects of building with a certain degree of lateral flexibility? Will the resulting bending introduce a negative curving effect? Will pilots be frightened by the “movement”?

The old way was to build a series of chassis, assemble test bikes, order a series of tires, and work with highly paid test riders to turn fast laps. Another way – adopted by former GP250 rider Martin Wimmer in the development of the MZ tubular chassis – is to apply stress to your chassis with a long steel bar and see where the deformations appear by equipping it with a multitude of dial indicators. It is undoubtedly just as effective and much less expensive.

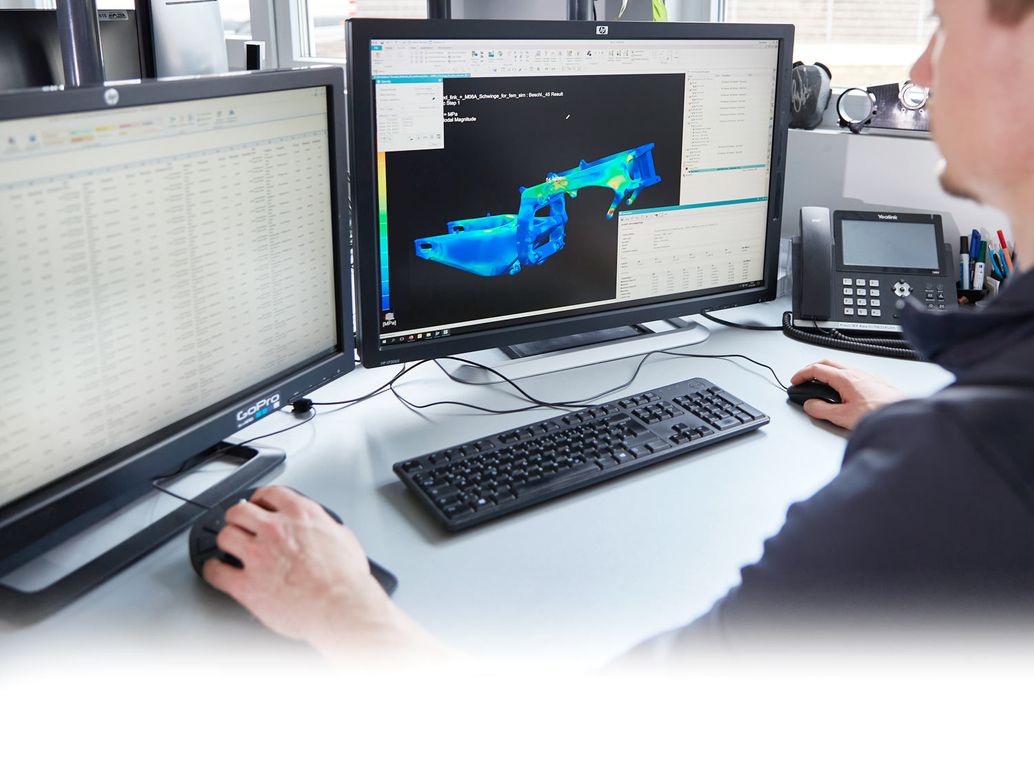

The digital equivalent is to model the chassis in finite elements and then apply the different constraints expected in the digital simulation. It is possible on some software to change the design dimensions in small increments and repeat the test, again and again through a large number of iterations, so that the desired values are achieved by successive approximations. This may seem otherworldly, but it's just less familiar to us than comparators and rules. Aviation has used these techniques for decades and now the low cost of computing is opening these tools to more users.

CAD allows engineers to make modifications and test more iterations of a chassis than would be possible through prototyping frames and applying physical stress

Kalex now has over 10 years of design experience, so when he applied his experience to a new unknown, namely creating a new chassis to incorporate the Triumph engine in 2019, during the first test of this chassis at Jerez, driver Jesko Raffin said after just five laps: “It looks like a Kalex. »

Thanks to the large number of chassis photos available on the Internet, we can study chassis from the past in a new light. The Honda RC30 Superbike has a massive steering column from which relatively thick, constant-section side beams emerge, all clearly intended to be stiff in all directions. At the time, it was the key to setting the best lap times in GP500.

The Honda RC30 is equipped with a very rigid chassis

This stiffness is now known to cause a vague forward feel and sudden loss of grip – as Ducati discovered with its super-stiff carbon chassis from 2009. The Honda RC30's chassis is magnificent – its machining and welds are of the highest quality. But it turns out it didn't work so well on pavement that wasn't smooth. This bike won the first two Superbike World Championships, largely because its acceleration was superior to that of its rival, the Ducati.

Kalex director Alex Baumgärtel explains philosophically: “Most riders say our chassis is softer than the Suter, while others say the exact opposite. We never tested the Suter for stiffness or geometry because you just have to go your own way. »

Álex Márquez, brother of current MotoGP champion Marc Márquez, was 2 Moto2019 champion on Kalex. Right now, Kalex's understanding of what a chassis needs to do to win championships comes closest to the ideal. We will see what happens in 2020, when the championship resumes its rights!

Photos © MotoGP.com & Kalex Engineering. Source: K. Cameron